The Discreet Bourgeois

Thursday, October 11, 2012

Tuesday, July 17, 2012

Qu'est-ce que c'est 'dégueulasse'??

I have been leading a monthly film group for the past several years. My intention is to show as many canonical films and shorts as possible. This month it was Breathless. Canonical for sure, but a film that I vigorously dislike. I diligently read up on the film and watched every last extra on the Criterion edition figuring that if I didn't come to like it, at least I could give good background beforehand and lead an interesting discussion afterwards. It is a landmark, after all, and just because I don't like it doesn't mean I won't watch and discuss it.

While watching and reading, I tried to understand why I disliked it so much. Often, you can't understand why you love something, but it should be fairly easy to figure out why you dislike something.

The first clue came when I read some excerpts of criticism Godard wrote before directing Breathless. Most of it came off as a manifesto or, even better, a war cry. Godard and his fellow critics were out to annihilate the established French directors of the previous era. They took affront at what they perceived as bad art. They had the right to excoriate because they were the true lovers of cinema and this establishment were talentless, flabby hacks who had no idea what cinema even was, let alone how to make good picture. Godard and the other boys of the Cahier du Cinema would show the world how it should be done, first through criticism extolling the virtues of the great American auteurs like Hitchcock and their Great God Howard Hawks, and then through their own films which came to be know as the Nouvelle Vague.

My next clue came from the dedication to the film to Monogram Pictures, a minor Hollywood studio specializing budget Westerns and things like Bowery Boys comedies. As the film unreeled, with its inside jokes about friends of Godard from his Geneva days and its obscure references to Sam Fuller films, it became clear what my problem was: Breathless is a very adolescent film. The whole aesthetic of giving the finger to the preceding generation, the praising of obscure films and directors to show that you have the gnostic insight to the true nature of film, all of this adds up, for me, to the feeling that I am spending time with a very petulant 18 year old.

Kathleen Rooney quite aptly points to a parallel between the punk ethos and what the Cahier guys were doing. In both cases what was perceived as a moribund art was given a jolt back into life by people who loved the art form more that life itself. The problem for me is that adolescent art doesn't age well and stops speaking to people who eventually grow up. I guess this is not a general feeling since Breathless is beloved by millions who watch it repeatedly.

Don't get me wrong. I am all for iconoclasm. I think Un Chien Andalou is one of the most subversive things ever created and I would watch it any time. Nor I am not totally down on Nouvelle Vague. The greatest cinematic experience of my life was when I first saw Celine and Julie Go Boating back in 1978. I have dragged more than one unsuspecting friends to sit through that three and a half hours of unalloyed bliss.

But Breathless seems to me like it just wants to sit in the corner and sulk. Yes, Belmondo and Seberg are pretty and sexy. Yes, the jump cuts are fun for the first half hour. But then it always seems to me that it is time for the grown-ups to leave the room and let the kids have their dyspeptic fun.

Monday, October 17, 2011

Your Next Best Film List

There is a list of 'best' films that no one seems to argue with. Best film of all times? Easy. Citizen Kane. Best musical of all times? Also, easy. Singin' in the Rain. Greatest comedy of all times? Some Like It Hot.

I am not saying that these are indeed the greatest, but they have been commonly received as such. Personally, I never found Some Like It Hot all that hilarious. I like Singin' in the Rain a lot, and I am always happy to watch it when it is on. But is it the greatest? Of course, the question is silly in that it is not quatifiable. I have compiled a list of movies that, for right or wrong, are universally acknowledged at the greatest of their genre and I have offered an alternative, just to expand your viewing options and let you join in in the best-film list silliness.

1- Your Next Greatest Film Of All Times - Citizen Kane is cited as the greatest film of all times, often by people who might not like it very much, often by people who have never seen it. The wonder of Kane is that it is a great film that is actually tremendous fun to watch. As an alternative, why not try The Magnificent Ambersons, the film that Orson Welles made after Kane? The Magnificent Ambersons doesn't have the stylistic dazzle of Kane. It is a subtler film. Its story is told in a linear fashion by an omniscient narrator, as opposed to the fun-house mirror narrative technique of Kane. The more traditional story-telling method gives the story and characters greater appeal than the endlessly fascinating but somewhat remote characters in Kane. The Magnificent Ambersons was a victim of RKO studio politics. The final edit was not by Welles and the final two scenes seem to belong to another film. Although more muted than Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons is still emotionally overwhelming. Agnes Moorehead's performance alone ensures its immortality.

2- Your Next Greatest Musical Of All Times - There doesn't seem any room for argument. Singin' in the Rain is the greatest musical of all times. Period. End of discussion. Yet..... Doesn't the Broadway Melody number go on way too long? Aren't the characters, while endearing, a little cardboard? Singin' in the Rain is so solidly recognized as the greatest that it almost seems heresy to propose an alternative. However, I submit for your consideration Vincente Minnelli's 1944 masterpiece Meet Me In St. Louis. The film has something that most musicals lack: a great book. It depicts the life of the somewhat quirky Smith in the year leading up to the opening of the 1904 World's Fair. The characters are well-rounded. The film has great period nostalgia and some sentimentality, but enough vinegar to keep the enterprise from becoming too cloying. The songs are a mixture of original and period compositions, and they flow organically from the action. There is a Hallowe'en scene that is genuinely creepy. A totally satifying film experience.

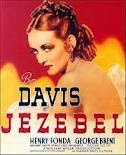

3- Your Next Greatest Historical Romance - Even ignoring the racial insensitivities and the romanticising of the Antebellum slave-owning Dixie, Gone WIth The WInd is a dull, elephantine work. As an alternative, try Jezebel from 1937, starring Bette Davis and Henry Fonda. Legend has it that Warner Brothers Studio created the film as a consolation prize when Bette Davis did not win the coveted role of Scarlett O'Hara. Davis' character is certainly as self-centered and headstrong as Scarlett, The MGM 'Tradition Of Quality' often can over-inflate a film. Here the grittier Warner Brothers production values make this a more engaging and satisfying film. The story is tightly told, the performances are wonderful, and it is all in glorious black and white

4- Your Next Greatest Adventure Romance - The favorite in this category must be Casablanca, a film I believe deserves all the praise and devotion it has garnered over the years. So, why not stay in the same mood with an alternative film? You say you like Humphrey Bogart thwarting Nazi operatives in the company of beautiful women? Why not try To Have And Have Not, based on what Hemingway called his worst book. The locale in Martinique is gritty in the best Waner Brothers fashion. The supporting cast is as wonderful as that of Casablanca, with a beautiful performance by Walter Brennan. What makes this stiff competition for Casablanca is the sexual fireworks between Bogart and Lauren Bacall in her film debut. Watching these two falling in love is a sophisticated pleasure.

5- Your Next Greatest Christmas Movie - Yes. I know. The greatest Christmas movie is It's A Wonderful Life. It is interesting to note that this 1946 film was not very popular when it premiered. Perhaps such a downbeat film coming right after the end of World War II was not what the public wanted. People had been through enough hardship and sacrifice and maybe were weary of this film's message of one's obligation to one's fellow man and the importance of sacrificing your dreams for others' well-being. I have found this film's message very troubling and have often voiced my dislike of it, courting physical danger from proponents of the Bedford Falls saga. Jimmy Stewart is on record as saying this is his favorite film of his career. I don't believe him. Not when he played the leads in Vertigo, The Shop Around The Corner, Rear Window and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. As an alternative, try Christmas In Connecticut from 1945. Much slighter than It's A Wonderful Life, it is also much cozier and sweeter. For a good dash of comedy you have supporting actors of the caliber of Sydney Greenstreet, S. Z. Sakall and Una O'Connor. Plus a love story centered on the very sexy Barbara Stanwyck and Dennis Morgan. I look forward to seeing Macushla every year.

6- Your Next Greatest Comedy - I do not like Some Like It Hot. I find it nasty, sexist and boring. I don't say this too loudly in public for the same reason that I don't express my true feelings about It's A Wonderful Life. However, I do love The Palm Beach Story by genius producer-writer-director Preston Sturges. This film is an absurdist trip down the rabbit hole worthy of Lewis Carroll. Insane situation piles up on top of insane situation, leading to an exhilarating, insane climax. Along the way, we encounter some of the wisest observations of love ever made. The dialog is so fast and so brilliant that you might not get just how brilliant this film is the first time around, but, lest you fear that it is simply a brainy comedy of manners, rest assured that there is enough slapstick to satisfy your baser comedy needs. Claudette Colbert and Joel McCrea's madcap journey from Manhattan to Palm Springs leads to mind-boggling encounters with a canvas of characters as varied as an oracular Pullman Car conductor, the Princess Centimiglia, the libidinous sister of the Rockerfelleresque Rudy Vallee and of course, the Wienie King, who is the closest I have seen to a Deus-Ex-Machina in American film.

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

Achieving Timelessness

The most discussed film of the past year must be Terrence Malick's The Tree Of Life. There was never any doubt that the film would be devoured by cineastes. Malick is a famously reclusive director who surfaces after long periods of silence with films of great beauty. Film lovers have ecstatic memories of their first viewing of his Days of Heaven (1978). With only five feature films in thirty-eight years, expectations for The Tree of Life were understandably high.

The film is stunning to look at, but quite cagey in its intentions. Just what is it doing? It seems to be concerned with depicting the life of a young family in Waco, Texas in the early 1950s. Their lives are presented in an impressionistic fashion. We don't get their story, rather we get the shape of their story. The film also attempts to put this very specific place and time in the context of the birth and death of the whole universe. A curious interlude with dinosaurs may echo tensions between the main character and his father. Scenes of the birth of planets contrasts with a highly stylized sequence at the end of the film where all the characters appear to be meeting beyond death in the shallow waters of a barren lake bed. Blissful scenes of summer evenings of childhood contrast with angst-ridden scenes in modern-day Houston's barren office buildings. The angst is never clearly articulated although it is effectively presented, just as the beauty of those summer nights is only evoked.

I left the theater dissatisfied. Subsequent attempts to get at the core of the film didn't yield much either. It is discussed in hushed, reverent tones and attempts to pin down its meaning are often dismissed as shallow efforts of a philistine.

The Tree Of Life left my consciousness quickly after seeing it. It wasn't until I recently watched John Ford's She Wore A Yellow Ribbon (1949) again that I began to re-engage with it. I was able to come to a better understanding of it through the lens of that Western.

She Wore A Yellow Ribbon is the second in a loosely connected series of films often referred to as John Ford's 'Cavalry Trilogy'. It follows Fort Apache (1948) and precedes Rio Grande (1950). The films are only connected in that they depict cavalry life on the frontier right after the Civil War. Curiously, the characters played by Ben Johnson and Victor McGlaglen have the same names even though they are not playing the same people from film to film.

The film takes place in a very specific time. The voice-over introducing the film informs us that Custer has just been killed, which places us in late 1876. The Indian Wars seem to be winding down, but there are still pockets of resistance from tribes fighting the encroachment of the white man on ancestral lands. The Civil War also casts a long shadow over the events of the film. Sgt. Tyree (Ben Johnson) constantly reminds us that he is a son of the confederacy and states that the letter of honor that Capt. Brittles receives at his retirement would be even more meaningful if it contained Robert E. Lee's signature along with Grant, Sherman and the others. The officer killed at Sudros Wells lies in state under the Stars and Bars.

This anchoring of the film into this specific era is done with a plethora of details of the time. The minute detailing of daily life, a hallmark of Ford films, is evident here in the depiction of life at Fort Starke. We go with the soldiers to the genearl store that doubles as a bar. Young officers and their girls go, or at least attempt to go on picnics. Friendships, rivalries and camaraderie among the soldiers is fleshed out by small, almost off-handed detail. Though unessential to the plot, dances, scouting parties and troop exercises give a great feel for life in that place at that time.

This very attention to detail has the dual effect of solidly locating the action in a time and place, but it also expands the everyday aspect of the film into the epic and timeless. Consider how She Wore A Yellow Ribbon depicts the whole spectrum of love and marriage:

a -The trajectory of the flirtation between Olivia Dandridge and Lts. Cohill and Pennell points to an inevitable marriage just beyond the end of the film. Here we see the budding romance ending in almost fairy-tale like coupling.

b- The mature relationship between Col. Allshard and his wife Abby, affectionately referred to as 'Old Ironpants', shows the quiet understanding and wordless communication that only comes after years of being together. They represent the high point of relationships.

c- As Olivia and her beaux show us the beginnings of love and marriage, the poignant visits of Capt. Brittles to the grave of his wife depict the relationship that exists even after death.

This multifaceted depiction of love and marriage lifts the movie into a timeless rumination of just what love and marriage is. It is no longer the story of these individual characters. It is the story of love itself.

The way that the various stages of military service are shown in the film also lifts it out of a particular time and place. The whole notion of 'career' is laid out before us.

a- She Wore A Yellow Ribbon begins with a clear statement that Nathan Brittles along with Sgt. Quincannon are soon to retire from active service. This is another of the trajectories that create the framework of the film. Brittles and Quincannon are career soldiers on the brink of the unknown. What will they do once they leave the cavalry? They look ridiculous in the suit of civilian clothes they both try on. Brittles talks off-handedly about going west, perhaps to California, but going west means going into the setting sun, and the setting sun metaphorically means one thing only.

b- But with then end of the career of these two hardened soldiers, the career of two green cadets on the rise. Cohill is poised to take the reins of command from Brittles. We are anxious about his inexperience and callowness, but as the commander says, everyone must make their first run cross the river under gunfire. He will gain his experience just like Brittles did.

c- The counterbalance to these two is Sgt. Tyree. He is a seasoned soldier at the height of his career. He, too, will be at the fort after Brittles has gone, but he will be gone long before Cohill retires.

The sense of epic is taken a step further with the hint of a past history, of things that happened before the story begins. This is so beautifully depicted in the scene at the camp of Chief Pony-That-Walks. Ford creates a sense of tension and fear that the situation could explode into violence. We are afraid because even the usually cool and collected Sgt.Tyree is visibly nervous. However, Brittle strides into the camp. What gives him the confidence? We soon see that he has an almost brotherly relationship with Pony-That-Walks. They are both relics of a time when Indians and white men, while not exactly friends, at least respected each other. They can speak each others' languages. They have smoked the peace pipe together.

The tragedy is that it is too late for peace. Our glimpse of Brittles and Pony-That-Walks as leaders of their respective men, is but a shadow of what they now are. Their civilized friendship is swept aside by the zeal of a new generation bent on the annihilation of the other side. Even though it is not shown, we know the history of these two men. By being able to sense what they were, we leave the 'present' time of the film and are aware of history rushing past them.

I feel that the concreteness of the depiction of time and place in She Wore A Yellow Ribbon allows it to accomplish what The Tree of Life tries to do, but ultimately fails to do. The obliqueness of The Tree of Life prevents it from attaining the epic and timeless, something that She Wore A Yellow Ribbon does with seeming effortlessness.

Tuesday, February 8, 2011

I'd Give My Head To Know What Really Happened Up There

This is all you can know, all you can be told. When you get where I am, you will know the rest.

-Sunny von Bülow, Reversal of Fortune

Demand me nothing: what you know, you know: From this time forth I never will speak word.

- Iago, Othello Act V, scene ii

Picnic At Hanging Rock presents a mystery that is never solved. On Valentine's Day 1900, three teenage girls from an upper class boarding school, along with one of their teachers, disappear during a day-trip to a local geological wonder. One of the girls reappears several days later with no memory of what happened. The other three are gone forever. Bits of information begin to appear, which we try to piece together in an attempt to explain the events of that fateful day, but they are contradictory and frustrating. The leads to any real resolution eventually run cold. The facts we are left with are flimsy and arbritrary. We can't make anything of them and we soon let go of any hope of solving the mystery.

Picnic At Hanging Rock uses this mystery to draw us into its world. The urgency to find out what happened is so compelling that we don't realize how immersed we have become in its universe. Once we come to know that we will never know the answer, we are beyond caring. We have become deeply involved in the lives of everyone depicted. The disappearance is a MacGuffin worthy of The Birds.

The opening scenes carefully depict a tightly buttoned world that has much bubbling below the surface. The rigid formality of the girls' school is soon to unravel. The budding sexuality of the students will give way to tragedy and hysteria. The placid young Englishman (Dominic Guard) visiting his dim, aristocratic aunt and uncle, will lose his Victorian impassivity in a burst of passion and yearning. The disapperance is a catalyst for all this. The way the bird attacks afford us a window into the complicated lives of Melanie Daniels and the burgers of Bodega Bay is comparable to the way the disappearances in this film enable us to have an intense identification with those left behind.

So often an unsolved mystery can be audience-baiting. One watches such films as Mulholland Drive or the series Twin Peaks, tantalized by the direction the clues to the various mysteries are leading. The clues to the mysteries of Twin Peaks or Mulholland Drive are as inconclusive as the clues in Picnic At Hanging Rock, but I believe the audience feels a betrayal in the Lynch productions. As we watch those works, we come to realize that not only are the clues red herrings, but the movies themselves are only about these red herrings. We are frustrated by all the work we are doing to bring it into some sort of order.

The reason that Picnic at Hanging Rock is so powerful is not that the mystery is unsolved, but that the mystery becomes irrelevant. The honest emotion we share with the protagonists is the true gift of this film. By having us identify so closely with the characters' need to know, we penetrate their psyches.

The various components work beautifully to mesmerize and overwhelm us.

The first element to make an impression is the haunting pan flute score by Zamfir. The music is odd and ancient sounding, reminiscent of the digeridoo. The unresolved, yearning melodies parallel the story.

The costumes are another critical elements in the character studies. Michael's three piece suit and top hat in the sweltering February heat emphasize how he is trapped in his late Victorian world. As he becomes obsessed with finding the girls, his dress becomes looser and more relaxed. The white dresses of the girls give them the aura of the Botticelli angel that we hear Mlle. de Poitiers talking of. We also know that under the dresses are the constricting girdles, one of which will be the 'clue' that ultimately tips the mystery into insolubility.

The gradual dishevelment of the helmet-like hairstyle of the terrifying Mrs. Appleyard (played, in a tour de force performance, by Rachel Roberts) does as much as anything to underline the unraveling of this Fury of a schoolmistress.

The film obsessively repeats images, each time having them loaded with more and more emotion. The final glimpse of Miranda at the end brings home to us how the compounding of disparate clues has actually brought us to a profound emotional climax.

The mystery has revealed everything.

Sunday, November 28, 2010

Show Boat - the musical that changed everything

The Importance of Show Boat

When Show Boat was presented in 1927 by Florenz Ziegfeld, it was unlike anything the great showman had yet produced . His legendary Follies were really just vaudeville shows on a grand scale, featuring popular headliners of the day in unrelated scenes. Legendary performers such as Fanny Brice, Will Rogers, W.C. Fields and Sophie Tucker did their acts along side huge production numbers featuring scantily clad young women. Ziegfeld was 'Glorifying the American Girl', he claimed. He also presented light musical comedies such as Sally and Sunny with music by Jerome Kern. These were shows with wispy plots that were usually just vehicles for the star in question.

In the early part of the century, musical theater consisted of vaudeville shows, operettas imported from Europe or minstrel shows. In the 1910s a new type of musical that was purely American began to be seen. Jerome Kern, along with lyricist P.G. Wodehouse, created a string of this light, American style comedies about young people on Long Island estates and their love troubles. Once again, wispy plots that featured amusing tunes for the stars to sing.

Kern approached Ziegfeld with the idea of adapting Edna Ferber's epic novel Show Boat with a book and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II. Amazingly, Ziegfeld agreed to gamble on a musical concerned with miscegenation, segregation, wife abuse and alcoholism. It was not only the subject matter that was revolutionary. The style was revolutionary as well. Songs grew out of the dramatic situation. True, the operetta roots of Show Boat are evident in songs such as You Are Love. However, the way that Can't Help Lovin' Dat Man grows out of the action in the kitchen scene, and how it comments sadly on Julie's situation and foreshadows what lies ahead for Magnolia, reveals a new depth for the musical. The light revue had been given a death-blow. The 'book musical' would assume prominence from that time forward.

The Pedigree of the 1936 film of Show Boat

There had been a 1929 film version of Show Boat that was largely silent, with some songs tacked on. It is a curiosity at best. The story differs greatly from the story of the musical, and the majority of the film features actors that had nothing to do with the musical's creation on Broadway.

MGM mounted a lavishly produced, Technicolor version of the musical in 1951, starring Kathryn Grayson as Magnolia and Howard Keel as Ravenal. These two leads sing beautifully, but there is not much chemistry between them. Ava Gardner is miscast as Julie. The fact that Lena Horne was available for the role and had sung a spectacular version of Can't Help Lovin' Dat Man in the Jerome Kern biopic Till The Clouds Roll By, gives a tantalizing indication of what might have been. The whole production suffers from what many feel are the great assets of the MGM musicals of the 1950s: lavish production numbers and big-name stars. The whole thing feels bloated.

The 1936 production produced by Universal is the great film version of this musical. At the time, Universal was known as the Horror Film studio. Show Boat's director James Whale already had tremendous success with a string of straight-forward horror films such as Frankenstein, The Bride of Frankenstein and The Invisible Man as well as the great satire of the genre, The Old Dark House. These films are all notable for an eerie, Gothic atmosphere which can be traced back to the German Expressionism which exerted such a huge influence on early 'serious' film. The atmospherics are there in Show Boat as well. Here, however, they are employed to highlight emotional scenes. A good example of this is the montage during Old Man River. First, we hear Joe singing the song in a naturalistic setting: on a dock surrounded by other workers. As the song reaches its climax, we get a series of abstract images of toil and punishment which could have come straight out of an UFA production of the time.

The cast is fascinating in that many are associated with the original Broadway production. Charles Winninger reprises his Captain Andy from 1927. Irene Dunne (Magnolia) and Paul Robeson (Joe) were not in the original, but were part of the tour and are forever associated with the roles. Alas, we don't get to see Edna May Oliver's Parthy, which she created on Broadway, but it is not hard to imagine how perfect she would have been in the role. The great treasure of the film is the preservation of Helen Morgan's performance as Julie. Morgan, a sensation of the 1920's, is a little old for the role now, her voice a little creaky, but her fragility in the delivery of the torch song Bill is magnificent. She was only to live five more years, dying in 1941 at the age of 41.

Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein wrote two new numbers for the movie, I Have The Room Above Her and I Still Suits Me. They are minor songs, but it is exciting to know that the creators of the show were still working on it as the movie was being filmed. Thus, it is both a reflection of the original, as well as a work in progress.

Blackface

As Magnolia's performing career on the Cotton Blossom itself blossoms, we get to see many of her performances. The scene between the school teacher and her beloved Hamilton is an affectionate depiction of what types of melodramas were being performed in the days of the Cotton Blossom. The histrionic acting and overheated dialogue seem right. The audience's reaction confirms this. The humor of the scene comes not from the film's condescension to the play, but to the woodsmen's reaction - their belief that reality is happening on stage. The play itself is performed almost in documentary fashion.

The same sort of care is given to reflect authenticity in the musical numbers that are performed within the movie. This does not refer to the songs that grow out of the action, like You Are Love, I Have The Room Above Her and Old Man River. Instead, it applies to the scenes that are showing performances, such as Magnolia's New Year's Eve premiere in Chicago. Instead of composing an original song for this scene, Jerome Kern decided to interpolate After the Ball. This song was composed in 1891 and was a sensation. It sold millions of copies of sheet music, the first song to have such success. It defined the era musically, and for Show Boat's 1927 audience, it would have been an efficient evocation of the era.

The cakewalk performed by Ellie and Frank is also danced to an authenic song of the period, Goodbye, Ma Lady Love. The dancing is staged in such a way as to recall the style of the minstrel shows that would have been current at the time the movie is depicting.

There is no question that Black musical and theatrical performance styles were the pre-eminent entertainment forces in the era being shown in the early parts of Show Boat. True, there was a strong tradition of operetta and opera at the time, but the home-grown entertainment was predominantly derived from Black styles.

Understanding the way the creators of Show Boat were striving to portray authentic musical numbers of the time, should help us to see Magnolia's Gallivanting Around with something subtler than a knee-jerk condemnation of the scene as racist and offensive. Yes, Magnolia is in black-face, yes, she is plucking on a banjo and yes, she is mugging in a bug-eyed fashion throughout. However,

this was a convention of the time being shown. The exaggerated cartoonish depiction of the characters in blackface had little to do with real Black people, just as the characters played by drag performers have little to do with real women. The caricatures of blackface are as irrelevant to our contemporary entertainment sensibility as commedia dell'arte is. The point that needs to be made here is that including a blackface scene in Show Boat is as appropriate as using the N-word in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Both are absolutely appropriate because the intentions behind both are not racist and do not intend to demean. Both intend to portray.

The critic John Lahr has summed this up beautifully, saying, "..describing racism doesn't make Show Boat racist. The production is meticulous in honoring the influence of black culture not just in the making of the nation's wealth but, through music, in the making of its modern spirit."

As further proof, Queenie and Joe, though secondary characters, are not stereotypes. Joe, in fact, moves through the proceedings in the role of Greek chorus, wisely commenting on what is happening. He gets the most famous song of the show, Old Man River. This song also has Black roots in that it is as close to a spiritual as a white man has ever written. The song defines the whole show - time floods on, regardless of people. The fact that this profound observation is put in the mouth of a Black man goes a long way to refute any charge of racism to which the mere depiction of a blackface number might give rise.

Tuesday, October 12, 2010

Who Kills the Beast? Beauty? Maybe Not.

From the moment the credits start, King Kong impresses as being ultra-modern. This seems an odd thing to say about a film that is 77 years old. I do not mean modern for our times, but modern for 1933. The credits are drawn in bold Art Deco lettering, which reflects the design rage of the day. So many of the films of the early 30s were heavily influenced by Art Deco design, so having the credits so drawn makes it seem as if the film is saying 'I am urgently of today'.

The contemporary cues pile up in the first part of the movie. Anne Darrow's out-of-work situation clearly reflects the Depression that was only then being felt by the population at large. The repeated shots of a glittering New York, the most modern city in the world, are a good offset to that most modern of constructions: The Empire State Building. This building will, of course, figure in the climax of the film in the legendary fight between Kong and the biplanes.

Once this modernity is sufficiently set up, the true conflict of the movie comes to the fore. The romantic journey to Skull Island results in the arrival in the picture of the great, primeval Kong. He is as much a wonder in his world as the Empire State is in New York City. Where the Empire State is a cold, steel and glass phallic presence, Kong is raw sexual energy. The inevitable meeting of the two hastens the climax.

Anne Darrow is the link between these two forces: aspiring star of Manhattan and love object of Kong. This is especially apparent in the scene when Kong pulls her out of her room in the building as he makes his ascent to meet his doom.

Kong in New York is a dangerous, disruptive force not just because he is big, but because there is nothing of the modern about him. He is ancient. He is sexual force incarnate. There is no place for him in Manhattan. As they say in the old Western, the town ain't big enough for the two of them.

Something has to give, and, alas, it is the mighty Kong.

The famous final line seems to be wrong. Beauty doesn't kill the beast. Modernity does.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)